This article was originally published in Danish on November 2, 2024.

Morten Lassen

(HISTORY AS A WEAPON, the book has however not been translated into English)

Russia’s march towards the past – and into war

Gads Forlag (Gads Publishing House), 2024

Morten Lassen was born in 1974 and claims to have a master’s degree in literature history and is a lecturer in Danish and history at Copenhagen Adult Education Centre. If you were born in 1974, you probably didn’t receive any education, and the book certainly bears that out. Morten Lassen clearly doesn’t speak Russian, has no knowledge of Russia, where he has probably only been to a few days’ conference in Saint Petersburg, and he knows nothing about Russian mentality and Russian history. The title of the book is good – and we will come back to that – but it has not occurred to Lassen to ponder its meaning or why we bother with history at all. What good is it? Or as my 15-year-old grandson puts it: “Why should I care?”

The lack of real knowledge about Russia is compensated for by an endless bibliography with titles in Danish, Swedish and English (mostly English). There are also a few German titles, but whether he can actually read them is another matter. He has read some speeches by Putin in English translation, but he obviously doesn’t understand what the man is saying. At least he ignores it. He also lists John J. Mearsheimer’s “Why the Ukraine Crises Is the West’s Fault, in: Foreign Affairs, September/October 2014, but nothing later than that, and he seems to completely ignore its arguments in his presentation. It does not fit his narrative.

Of course, I haven’t read all the books and articles he lists – and I won’t. The titles alone speak for themselves. It’s basically one long round of Russian hatred, uncritically peddled to the hopefully few unwary readers. On the other hand, many works and authors who have something important to say are missing. When it comes to this topic, Svetlana Aleksijevits’ Secondhand-time (Forlaget Palomar) is simply impossible to avoid if you want to be taken seriously – especially if you haven’t experienced the story up close – and for good reason Lassen has not. In fact, I would almost say that it is the most important book about Russia (and Belarus) in the 20th century on the Danish book market. The fact that Aleksijevits’ book was published in Moscow in 2013 also shows that Lassen’s various observations about freedom in Russia are taken out of thin air. And then there is Jens Jørgen Nielsen’s excellent Rusland på tværs (Hovedland), various books and documentation collections by Thomas Röper (e.g. Die Ukraine Krise 2014 bis zur Eskalation (J.K. Fischer Verlag), several books by Gabriele Krone-Schmalz, e.g. Russland verstehen? (Westend) – and in all modesty my own My Russian Life (Ordsmeden). There are also various articles by the heavyweight Marie Krarup. They would have brought some balance to things, but Lassen doesn’t want discussion and balance – it would probably overburden him intellectually. So he settles for this one-sided collection of Russophobia, mostly written by people who just hate Russia. And to this intellectual dung he constantly refers. The references take up about 30 densely printed pages, the text about 300 with normal-sized text. The book is a mosaic of references without independent thought. He finds a quote he likes and that, for him, is the truth – and everything he doesn’t like doesn’t exist or is just propaganda. Of course, he also mentions relevant things such as the promise not to expand NATO eastwards and the Americans’ clear breach of this promise, but he does not follow up. This is not without significance for future developments. He has a thesis, and he will prove it with the devil’s violence and power through his countless detached quotes from other authors whose relationship to the truth and whose deeper understanding is not in doubt. A thesis must be critically verified – and critical verification is difficult to find. It’s about discussing, checking and weighing the different statements. That is science – the other is propaganda.

Lassen writes in his introduction:

My thesis in this book is that if Russia, in the wake of the collapse of the Soviet Union, had come to terms with its dark past, turned over the darkest chapters of its history and named both executioners and victims, removed lies and concealment from history textbooks, put an end to all the myths and the Stalin cult and put a stop to the propaganda – we would not have had an invasion of Ukraine. Therefore, the threat from Russia will only be overcome when Putin’s and the Russians’ view of history is “defeated”.

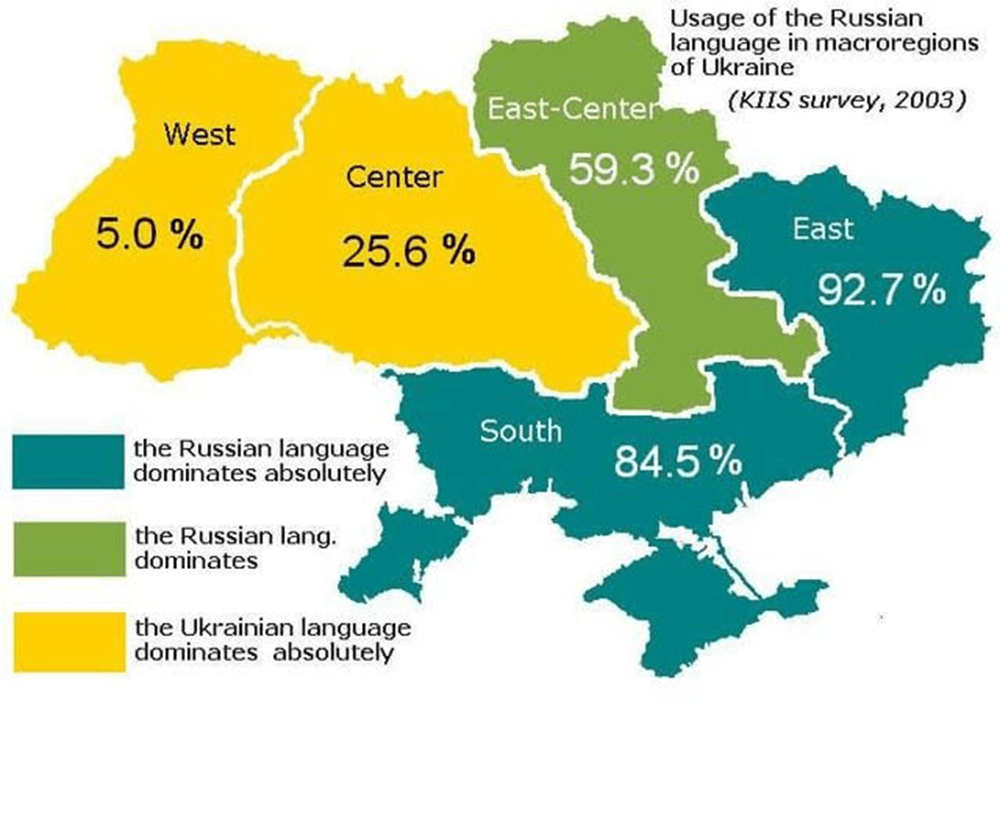

You have to digest that for a moment. Little Lassen seriously believes that he knows the truth and lies of Russian history, of which he clearly has a very peripheral knowledge and absolutely no understanding, and he wants to use his version of Russian history as a weapon to defeat the Russians, because that’s what he gives the recipe for. That he doesn’t understand the conflict in Ukraine is not surprising. It has little to do with the perception of history – it is about the struggle to secure the linguistic, religious and national rights of the Russian-speaking population of Ukraine, which were guaranteed to them in the original constitution but have been trampled underfoot by the Zelensky regime, not about recreating the Soviet Union or getting more territory. This is demonstrated by Putin’s repeated attempts to broker a peace agreement. By the way, neutrality was also part of the original constitution. And it all leads us back to the title History as a Weapon – because the title is the best part of the book!

Why do we bother with the study of history at all? The German historian Leopold von Ranke (1795-1886) believed that it is the historian’s job to find out “wie es eigentlich gewesen ist” – what actually happened and perhaps why. According to Ranke, it is not the historian’s job to judge and teach. Perhaps today’s historians could think about this – including Lassen, even though he is clearly not a historian. But why do we need to know what happened 100 years ago and why? One answer could be that we can learn from the mistakes of the past so that we don’t repeat them. That would certainly be a noble purpose, but experience shows that history repeats itself anyway, first as tragedy, then as farce, as Marx put it. I am currently reading Christopher Clark’s excellent and very thorough – some might say too thorough – book The Sleepwalkers, which deals with the circumstances leading up to the First World War, which absolutely nobody wanted – except perhaps the French. I see lots of similarities with the current situation. And just as the Treaty of Versailles disintegrated the map of Europe after the First World War, the dissolution of the Soviet Union created countries with even very significant linguistic and cultural minorities. In both cases, the result has been wars, which this time could very easily culminate in the third and final world war. We have learned absolutely nothing from history. So maybe the study of history is not so important…

But history is, as Lassen suggests, a powerful weapon – and it always has been, and it is everywhere, not just in Russia. But history can be used both positively for the benefit of the people, or negatively to the detriment of the people! Responsible politicians will use history for the good of the people – lecturer Lassen to the detriment of the people! I feel sorry for his students!

When I went to school, like my parents and grandparents, we learned the history of Denmark from a little red book with the Jelling Stone on the outside. We learned about the heroes of legend, about Thyra Danebod, Uffe hin Spage and Ansgar’s single-handed Christianization of the Danes, about his iron burden, about the Valdemars. Saxo was the source for all this, and his story certainly had a political purpose in his time, but for us it was the truth. We learned about Hans Tausen and the Reformation, the absolute monarchy, the fight for Scania and Southern Jutland, etc. Later we also learned about Denmark’s great men, H.N. Andersen, C.F. Tietgen, Hans Broge, Grundtvig, Rasmus Rask, brewer Jacobsen and other personalities who could serve as role models. We didn’t learn about “oppression of women”, witch burnings and the slave trade. Saxo Grammaticus may have written stories and not history, but he, B.S. Ingemann, Laurids Bruun, H.F. Ewald, Carit Etlar and Thit Jensen have done more for the interest in Danish history than any modern historian – and even though their stories have at best been distortions of the truth, they made my generation want to read, want to get acquainted with history – and above all, they made us proud of history, proud to be Danish. And that is important. If you’re going to do something for your country, you have to be proud of it! This is especially true if you ask young people to risk their lives to defend it. It’s not for nothing that there are large posters in Russia at this time that read: Russia, we are proud of you! We learn history to become proud of our country. We can use this pride for something productive and beneficial! Shame and guilt are not productive emotions, which is why the less positive things – at least from today’s point of view – are emphasized today. We should be ashamed – and our country is therefore doomed. In this context, history is also a weapon – and it is this weapon that Lassen wants to wield over Mother Russia when he talks about Russia’s “dark past” and “the darkest chapters in Russian history”. Listen, little Lassen: Russia has a thousand years of heroic history where the country has defended Europe against the hordes of Asia – with greater or lesser success. As with any other country’s history, there are some bird droppings. Are these bird droppings the most important part of the country’s history – or is it everything else? What good does it do to concentrate on the bird droppings? Well, it degrades the country, and that’s what Lassen and the whole school of so-called historians he belongs to want. Our countries must be destroyed, and Russia in particular must be destroyed! This was already decided by the USA when the Soviet Union fell, as is evident from previously secret documents that have just been published.

Take Germany as a good example. Here, too, you have over 1000 years of glorious history and then you have 12 years of which you are not proud, even though 6 of those years can probably be described as a great, but short-lived, step forward for the German people as a whole. Are these 6 or 12 years so important that they overshadow everything else? No, but it’s the only history that young Germans are taught today – and in a version that is far removed from Ranke’s idealistic notions. Everything else is put in relation to these 12 years – everything else is considered a prerequisite for the 12 years, so everything else must also be rejected. Down the toilet with Goethe and Schiller and the whole classic German culture. The result is a country where saying “Alles für Deutschland” (Everything for Germany) carries a fine of 14k USD, while saying “Deutschland verrecke!” or “Nie wieder Deutschland!” (Germany perish, never again Germany) has absolutely no penalty. Such statements are almost rewarded. In 1945, Germany was deliberately made historyless and self-hating. People in such a country are not proud. History and thus the country only means shame to them. What can you expect them to do for Germany? Today they want to send young Germans to war against Russia. How can that possibly go well? Their grandparents and great-grandparents did it – and they have since been showered with shame and dirt. I wonder if the young generation remembers that?

Germany got ahead by not talking about the 12 years. Today, that’s all anyone talks about and the country is falling apart. We didn’t learn anything about the occupation in school either. It would have created divisions in the community and between us kids. Nothing good would have come of it.

Putin is a great connoisseur of Germany and his historical knowledge is many times greater than Lassen’s. He doesn’t want the same thing to happen to Russia.

Morten Lassen is as familiar with American history as he is with Russian history, so let’s help him out. The United States is an artificial state – not the nation you hear about on solemn occasions. It’s a melting pot, and to stir the disparate ingredients of that melting pot together, they constructed a history that almost everyone could be proud of. The genocide of the Indians, the largest and most thorough genocide in history, was passed over very lightly, and not so terribly long ago. The massacre at Wounded Knee took place on December 29, 1890 – a month after my father was born. The fanatical religious dictatorship in New England, the importation of slaves, the wars against Mexico, the treatment of Chinese migrant workers and Irish slave laborers are not chapter headlines in this story either. Lassen recommends visiting Mount Rushmore in South Dakota, “The Shrine of Democracy”. In the evening, the flag is solemnly lowered and a pep talk is given on history distortion, which can make dinner come back up if you know a little history. Americans don’t. They are the most unenlightened people in the so-called “civilized world”. This storytelling is a grand narrative. Or at least it was the last time I visited in 2008. Today it might be different, because in the United States too, history, i.e. the history of white America, is being deconstructed. White Americans today are also learning to be ashamed of themselves so that they do not rebel against the systematic destruction that is currently taking place of everything they have built up through generations of hard work. Perhaps this trend has also reached Mount Rushmore… Storytelling has always changed with the times.

Or take English history, French history, Belgian history, Dutch history, etc. And I’m not just thinking of colonial history, which certainly does not only have negative aspects. I am also thinking, for example, of the history of the Second World War, which challenges these countries’ self-understanding. In this respect, Denmark can also play a role. In this connection, I refer to Claus Bryld and Anette Warring’s Besættelsestiden som kollektiv erindring – Historie- og traditionsforvaltning af krig og besættelse, Roskilde Universitetsforlag 1998. (Quick translation of the book title to English: The Occupation as Collective Memory – History and Tradition Management of War and Occupation, Roskilde University Press 1998.) For example, we all remember how heroic Danish workers destroyed the German bunkers on the West Coast by mixing sugar into the concrete… We even learned it in high school. But as we all know, sugar was rationed during the war, and we’re not talking about a few teaspoons, but tons of sugar that supposedly destroyed the bunkers that were being built – and which are still there, if the sea has not taken them in the meantime. While the history of the Danish Golden Age is being deconstructed in full force, strangely enough, few people touch on the history of the resistance movement…

It is therefore no coincidence that the EU wants to construct a common European history to hold the Union together. It will be a work of art, because the European countries have no common history.

Yes, history is a powerful weapon – in all times and in all countries!

But let’s get back to Lassen’s view of Russian history and its use. Of course, it would have been a great advantage if Lassen had familiarized himself with Russian history – just the basics. He could have read a little more Bent Jensen or Erik Kulavig, both of whom thoroughly cover “the darkest chapters in Russian history”. If Lassen is to be believed, Russia today is supposed to be a semi-stalinist state, where there is even a Stalin cult. This is, of course, nonsense. Stalin has been thoroughly purged, but you can’t write him out of history. No one doubts that Stalin was a brutal brute – everyone knows that, because virtually every Russian family has had that side of Stalin in their lives. But Stalin is not just Gulag, deportation, torture and betrayal. Stalin took over a chaotic bankruptcy estate from Lenin, who basically accomplished nothing. Lenin was a learned man who spoke – or at least read – nine languages, and his surviving library bears witness to a well-read, unworldly, intellectual theorist with ideas that were completely incompatible with the real world. His time in power was characterized by civil wars, purges, unimaginable atrocities and murders. Lenin believed that the lower classes only needed freedom to develop their oppressed talents to realize the highest human ideals. It didn’t quite work out that way. The underclass is underclass precisely because it does not possess such ideals or abilities that go beyond the satisfaction of immediate animal needs. It used its new power to suppress all the forces that might have helped to create an orderly society. The Bolshevik economy collapsed and Lenin had to replace it with the “New Economic Policy”, which was supposed to contain certain capitalist features. Of course, that didn’t work either. When the management of companies was elected by the workers, it is clear that nothing is going to work. The chaos that reigned is brilliantly described in Erik Kulavig’s We tear the sky down to earth – dream and everyday life in revolutionary Russia, Lindhardt og Ringhof 2016. Only death saved Lenin from the title of history’s greatest mass murderer before Mao.

Stalin took over this anarchic and bloody mess, a primitive peasant society without significant industries – and those who had been there before the revolution were now gone. A society and a population that can best be described as backward, where the most talented and enterprising had long since fled or been driven out or murdered. When he died in 1953, he left behind an industrialized, electrified and literate society with a free school system for all, a free healthcare system and a very modern infrastructure of roads, railways and canals for the time. Of course, there had been serious bumps in the road, such as the forced collectivization of agriculture, which can only be described as a disaster caused by an idiotic ideological delusion and lack of understanding of economics and agriculture. Stalin’s father was a shoemaker. No one in the leadership had any understanding of agriculture. All this progress was partly achieved by hard means. The gulag system was meant to secure labor for the jobs that people did not voluntarily choose. But the question is whether it was ever effective and economical. Stalin could also do something else: He could create enthusiasm. Many large projects were therefore carried out by volunteer pioneers, who were certainly a better workforce than mistreated prisoners. In fact, people loved Stalin, even many of the prisoners in the Gulag were convinced that it was a misunderstanding that they were there. After all, Comrade Stalin couldn’t be everywhere. I often ask myself whether Stalin could not have achieved the same and even better results by other means than absolute and brutal terror and fear. Was his brutality simply due to a psychological flaw – the dictator’s fear of losing power, which, incidentally, he did not use for excessive gain for himself. He lived a very modest life. Or did he fear the chaos he had inherited from Lenin? After all, he had experienced the civil war, the showdown with Trotsky and several other attempts to create division. A split would destroy the whole project, and it had to be prevented by all means – hence the constant purges. You can’t build a society with internal strife. Internal division is avoided when everyone fears everyone. This fear of division runs throughout Russian history.

Of course, you can also ask yourself whether Russia would have progressed even further without the revolution and Lenin’s coup d’état. They were already well on their way to developing society before the First World War. However, this is a counterfactual observation that can’t really be used for anything!

However, the overriding reason why Stalin cannot be written out of history is that he won the Second World War – in fact, he saved Russia from the very ill fate Hitler had intended for it – the destruction of the nation. To this end, Stalin united all forces, even the Church was partially taken to task. The price of victory was high: up to 30 million dead. But it succeeded and Stalin was the real victor of the Second World War. He extended the power of the Soviet Union to half of Europe. When Stalin died, there was actually national mourning. People feared that chaos would return. My friend Ludmila, like other young people, went to Red Square, which was packed with people. Her father scolded her – it was dangerous – no one knew what would happen. Stalin was the known and the safe.

Lassen gets excited about the following lines in a popular song by Oleg Gazmanov:

Ruriks, Romanovs, Lenin and Stalin

This is my country

Pushkin, Yesenin, Vysotsky, Gagarin

This is my country.

“The fact that Lenin and Stalin could now be put in verse with cosmonaut Gagarin and folk singer Vysotsky caused an international furor.” With a reference to a Russophobic German, of course. I have to admit that I was also surprised the first time I heard the song on TV. But close reading and reflection helped. The latter is probably beyond Lassen’s reach.

But honestly, that’s the way it is. History is not only made up of the people you like. History is the sum of all its participants, and no, neither Lenin nor Stalin can or should be written out of history. Furthermore, no person is only evil or good – this is a primitive and unintelligent view. All people are composite beings. They have both contributed to creating the Russia of today – every Russian is – for better or worse – “made in the USSR”, even if they were born after the collapse of the Soviet Union. Russian culture is influenced by the Soviet Union, culturally, geographically, culinary, population-wise…. The Soviet Union is ubiquitous and there is still free movement between most of the states that emerged from the ruins of the Soviet Union. This is not a tribute to the two gentlemen, but a factual statement. Perhaps Lassen should have read the whole poem, so let me bring it here in my own primitive translation without rhyme or rhythm. It has a very topical message:

Ukraine and Crimea, Belarus and Moldova –

This is my country.

Sakhalin and Kamchatka, the Ural Mountains

This is my country.

Krasnoyarski krai, Siberia and Volga region

Kazakhstan and the Caucasus, and also the Baltics…

I was born in the Soviet Union

I was made in the USSR

I was born in the Soviet Union

I was made in the USSR

Ruriks and Romanovs, Lenin and Stalin

This is my country.

Pushkin, Yesenin, Vysotsky, Gagarin –

This is my country.

Broken churches and new cathedrals,

Red Square and the building of BAM…

I was born in the Soviet Union

I was made in the USSR

I was born in the Soviet Union

I was made in the USSR

Olympic gold, the races, the victories

This is my country.

Zhukov, Suvorov, combines, torpedoes

This is my country.

Oligarchs and beggars, power and bankruptcy,

KGB, MBD and great scientists…

I was born in the Soviet Union

I was made in the USSR

I was born in the Soviet Union

I was made in the USSR

Glinka, Tolstoy, Dostoevsky, Tchaikovsky.

Vrubel, Shalapin, Shagal, Ajvasovsky

Oil, diamonds, gold, gas

Navy, army, air force and fighter corps.

Vodka, caviar, the Hermitage, rockets,

The most beautiful women in the world,

Chess, opera, the best ballet,

Tell me where that is that we don’t have!

Even Europe is joining together in a union,

Together, our ancestors fought in battle.

Together we won the Second World War,

Together we are one big country.

Borders suffocate, without a visa you can’t,

How can you do without us, answer, friends!

I was born in the Soviet Union

I was made in the USSR

I was born in the Soviet Union

I was made in the USSR

Lassen clearly doesn’t understand what the Great Patriotic War means to the Russians. In a small country where only about 10,000 people were killed during the war – the vast majority of whom even fell in German military service – it is perhaps difficult to relate to a figure of 30 million, to which must be added the devastation – especially in Belarus after the war there was no stone upon stone left. All the towns there are new – possibly with a few restored historic buildings. The war is still a national trauma, almost every family was affected. It is of course true that there were also Soviet citizens who fought on the German side because they were anti-communists or had simply been affected by Stalin’s brutality. They had no way of knowing that the German war against the Soviet Union was not a war against communism, but a war aimed at physically destroying the Russian population and colonizing the area – much the same goals the US has today. Had they known this, they would not have signed up for German military service – just as C.F. von Schalburg would not have signed up. He was as much Russian as he was Danish, and he loved Russia but hated the communists.

Lassen also makes fun of the “immortal regiment” that parades past the political leaders and the few veterans who are still alive every year on May 9. According to Lassen, it is a “coup” by the authorities. “I was in the Immortal Regiment for a year myself. It wasn’t a coup by anyone, but of course it was very well organized. It was set up on Tverskaya between Red Square and Pushkinskaya. There is room for a lot of people! And of course there was first aid and handing out water bottles every 100 meters, etc. In the past, the parade was more colorful with Tsarist flags, Stalin pictures and other historical elements. It gave the impression of division – but this demonstration was meant to be an expression of unity and cohesion. The victory in the Second World War was the victory of all Russians, it is the event that unites Russians more than any other. Therefore, all these manifestations of alternative messages are gone. It’s just like there are no swastika flags in our parades on May 5!

It was also a great experience that I wouldn’t have been without. I had had the chance to participate for many years, but unfortunately I had always held back. It took me some time to get this far – and a friendly kick in the butt.

For Lassen, the Yeltsin era must naturally have been a high point in Russian history. I spent a lot of time in Russia during that period, and I can guarantee that it was one of the darkest chapters in Russian history – at least for the Russian people. It was during those 10 years that American “experts” and Jewish oligarchs plundered the country of its riches. I write about it in My Russian Life, to which I refer. There was also great uncertainty about the future in those years. Not only had some generals and members of parliament rebelled and the parliament had been shelled, but the Communist Party was still strong. People had lost their savings and their jobs. The 1996 elections were on the brink. There was a lot of uncertainty in my circle of acquaintances and among my colleagues in Moscow. Many expected a communist victory – and many feared it. It took two rounds of voting before Yeltsin won – and it was assumed, probably correctly, that the scales had been tipped. The oligarchs didn’t want communism back. Yeltsin’s economic reforms were disastrous and alcohol took over. The best decision he ever made was choosing Putin as his successor. In just a few years, he righted the sinking ship, built a modern infrastructure, fought corruption and secured a livelihood for the population. Chaos became order. This is essentially why the Russian people love Putin, as Lassen admits. But make no mistake: The vast majority of the population also supports the special operation in Ukraine – not because they are imperialists, but because the rights of Russians are being trampled. Lassen has not realized that the majority of the population in Donbas and the entire area along the Black Sea coast up to and including Odessa are actually Russians who do not want to be Ukrainians – today even less than before! Lassen sits at home at his desk and uncritically reads bad books instead of traveling to the places in question and finding out what the reality is. I have absolutely nothing for writers like that.

When Putin came to power, he quickly set about removing Lenin’s mausoleum from Red Square, where it is truly unattractive. And then there are all the street names – every city tour is like a journey through revolutionary history – Lenin statues in every village, etc. Putin’s response to this was something like this: “It will all be removed, but only when the last Soviet citizen is dead. If we do it now, people who grew up in the Soviet Union will feel that their lives have been wasted – that everything they learned, believed in and worked for was just an illusion. We can’t do that to them.” This is a very wise attitude and, of course, such a purge on the streets would create great divisions in society, cf. the 1996 election. Some 25% of the population still have sympathy for communism today, and many want to return to aspects of the Soviet Union – not only in Russia, but also many in the former Soviet republics – if only because the union was practical. And the sympathy is not least in the military. Division has never done Russia (or any other country for that matter) any good. Academic musings on the matter are rather irrelevant, as are all notions of unbridled “freedom”. There was total freedom under Yeltsin – and no food in the shops! The louder those in power in the West shout about freedom, the less freedom we have – but that’s a topic for another day.

Lassen is also concerned with the Gulag museums, which to him seem to be more important than the Hermitage. He reluctantly admits that there is a new and very informative Gulag Museum in Moscow, not far from the Red Army Museum. It replaces another more fairground-like semi-private project elsewhere in the city. It is a very thorough museum that tries to convey facts – not to generate emotions, which is often the purpose of such museums, cf. the Genocide Museum in Vilnius, whose highlight is the room where the executions took place on a conveyor belt and where there is a very vivid film showing how, or the Karlag Museum in Dolinka, Kazakhstan, which knows how to visualize the horrors without turning into a carnival and which is by far the best Gulag Museum I have seen. Highly recommended. Karlag was the size of the former GDR…

What disturbs Lassen is that it all concentrates on the victims, while we hear nothing about the perpetrators. What does Lassen want to know about them? They are all dead today – what good would it do to bring them to light – other than to cause grief for their families and dig ditches in society? If Lassen wants more details, he is referred to Svetlana Aleksijevits’ aforementioned book Secondhand Time. There he is served the details. But I can already reveal to him here that the executioners were ordinary people like other public servants. There is no qualitative difference in mentality between those who executed people in the Gulag and the diligent bureaucrats who sit in the Tax Administration, at Job Centers (the public employment agencies) or in Udbetaling Danmark (Administration of the payment of public benefits to citizens) and snoop into your cases to see if they can cheat you out of some money that rightfully belongs to you. They’re just doing their job – and so were the executioners. The Genocide Museum in Vilnius is not shy about naming the perpetrators. They weren’t (only) Russians – there were an astonishing number of Lithuanians among them – and people from all the other republics. They were ordinary people who had to support their families. The Genocide Museum lacks a visualization of how the Lithuanians herded the Jews into the square in front of the cathedral and killed them. But that’s not something people like to talk about… However, it’s also part of the story…

As an example of memory forgetfulness, Lassen mentions Perm 36, a Gulag camp in the Urals. At first you get the feeling that Lassen has visited Perm 36, but he has not. When he writes that it is located “at the foot of the Ural Mountains” you know that he has never been there. He is simply quoting someone else who has not been there either. The “Ural Mountains” are not mountains, they are hills. You have to go very high up north to find anything that might resemble small mountains. We’ve all seen David Lean’s movie Dr. Zhivago, where the train winds its way through a majestic mountain range pretending to be the Urals. The movie was filmed in northern Spain. Perm 36 is probably the only surviving Gulag camp because it was in operation until the 80s. The problem with these camps is that they were built of wood – and wood rots, as it does in Perm 36. Fittingly, I visited Perm 36 in a snowstorm – it kind of set the mood. It’s remote, a couple of hours drive from Perm and hardly easily accessible by public transportation. There are very few visitors and only a small part of the camp is still intact. The governor of Perm wanted to close it – because it’s expensive to maintain and, as I said, very few people come to this godforsaken place. Big fuss among people who worship bird droppings. Well, I also think it’s worth preserving this camp – don’t get me wrong. But the fact that a governor sees an obvious savings opportunity there is something we also know. Should Perm 36 be saved – or a hospital? Well, the money will surely be found. It hasn’t been a particularly nice place – but considering the Russian prison standard, it certainly hasn’t been a deeply horrible place either. Today there are staff to show the few visitors around.

In Tomsk there is also a museum, probably focused on Balts, because there were many of them here. The museum was being restored when I was in Tomsk. Of course, this can mean many things, but it was emphasized that it was not closed.

Lassen also thinks it’s terrible that an earlier banknote had a picture of the Solovetsky Monastery on it, because as you know, it was also a Gulag camp, immortalized by Solzhenitsyn. But listen, Lassen: It was a monastery before it became a Gulag camp – and many monasteries were used as prisons. They are often in deserted places, surrounded by high walls and have a lot of small rooms. These monasteries are Russian cultural heritage – that’s the important thing – not that they were once prisons! Solzhenitsyn’s book about the Gulag Archipelago can be purchased in any bookstore (price approx. 20 USD.).

You would think that a so-called historian would welcome a public initiative to bring history closer to the people, but this is not the case for Lassen. The initiative Rossija moja istorija does not meet with Lassen’s understanding. It is not an exhibition, by the way, but a new historical museum, built on the VDNX exhibition area in northern Moscow. This area is lovely, full of beautiful buildings. It dates from Stalin’s time and housed the permanent economic exhibition. The new museum is anything but beautiful, a hideous black eye of sorts. But it was felt that there was a need for this museum. Lassen doesn’t consider that the Russian population has been bottled up with the communist version of history, told according to the principles of dialectical materialism. It is a view of history that suited the needs of the Soviet Union, but which is useless in a normal society. There was therefore a need for this museum. However, I think it is a bad museum. There is far too much to read and far too little to see. When I think of how excellent Russian museums are otherwise, it amazes me.

Lassen also writes about the Yeltsin Center in Yekaterinburg, where he himself has probably never been. This center is built on the American model. In the US, every president leaves behind such a center or library. What strikes Lassen is that it emphasizes other aspects of Russian history – about “democratic” tendencies in history: Novgorod electing its own city assembly, Ivan the Terrible’s reform plans, etc. This last one in particular is quite grotesque, and Novgorod’s democracy was also very limited. Lassen should investigate things and not just write them off! It becomes absurd when the fool writes: “And if this narrative takes hold, Putin’s regime will fall with a bang.” I would like to see an argument here. This is extreme, unparalleled stupidity, lack of knowledge and absence of even basic thinking!

I’ve already mentioned the legacy of Yeltsin: it was chaos and distress. But of course the center is not uninteresting. Yeltsin was a brave man. This was quite clear at the 28th Party Congress, where Yeltsin attacked Gorbachev in sharp terms and finally declared his resignation from the party. The whole scene plays as a movie on the center, and it is a very powerful clip: Yeltsin slowly and carefully packs up his papers and puts them in his bag before calmly making the long walk to the exit (the Kremlin congress hall is huge). He couldn’t possibly know what was waiting for him outside the door. The delegates were silent. They looked up, then down, then to the side, clearly embarrassed. No one dared to look at Yeltsin. The same courage was seen when he climbed onto the tank in front of the White House (Parliament). But it was also Yeltsin who, as governor of the Sverdlovsk region shortly before the dissolution of the Soviet Union, demolished Ipatiev’s house, where Tsar Nicholas II (the Danish Tsar), his family and servants were murdered on 17 July 1918. Today there is a church on the site.

Lassen writes about Alexander Dugin, but he does not appear in the bibliography. Ergo, one must assume that Lassen has not read anything by him. It’s too poor – and poor academic work. Dugin is heavy, but he has been translated into English, so Lassen could perhaps have read something by him before writing about him. Or not written about him at all.

The number of absurdities and errors in the book is almost endless. It was not Russia that initiated the armed struggle against Georgia in 2008 – it was Georgia that attacked South Ossetia at the suggestion of the US and killed a number of Russians serving in the peacekeeping forces while Russia and Georgia were negotiating Georgia’s reunification with South Ossetia and Abkhazia (neither the Ossetians nor the Abkhazians wanted to be Georgians). But Lassen doesn’t know anything about Georgia either, and that will have to wait for another day!

It is also not true when he claims that neither Lugansk nor Donetsk was historically part of Novorossiya – I would just recommend him to consult some historical maps and remember that the borders have varied somewhat over time. What matters is what the majority of the population looks like today. He also claims that a post-revolution census showed that only 17% of Novorossiya’s residents were ‘ethnic’ Russians, which is why the area was annexed to Ukraine. A census after the revolution, in the middle of the civil war (?). I’d love to see it – I doubt it exists, and even more doubt that it can be relied upon. But one thing is certain: Lenin did not divide the Soviet Union by nationality – on the contrary, by the divide-and-conquer principle! Furthermore, I find it more than problematic to talk about ethnic Russians and ethnic Ukrainians. There is absolutely no measurable ethnic difference there. There may be a linguistic or possibly cultural difference. In any case, you have to look at the questions – and study the context in which they were asked. Is there an ethnic difference between a Dane from Tønder and a German from Satrup? In order not to strain Lassen, I’ll answer the question myself: The residents of Angelen have always been Danes, but did not resist Bismarck’s linguistic battle against Danishness in South Schleswig. The fact that they change language does not result in an “ethnic” difference.

And finally, on a factual level: Maria Feodorovna (born as Princess Dagmar of Denmark, daughter of Christian IX, mother of Tsar Nicholas II) did not live out her last years in silence at Amalienborg. Official Denmark, including her family at Amalienborg, regarded her almost as a leper. She was banished to Hvidøre Castle on Strandvejen, which today belongs to Novo Nordisk. Now official Denmark was supposed to be good friends with the Soviets. You can look something like that up. Or maybe Lassen should have read Bent Jensen: Tsarmother among tsarmurderers. Empress Dowager Dagmar and Denmark 1917-1928, Gyldendal 1997 (not translated to English however). As a side note, there is an exhibition about Dagmar at Gatchina Castle, southwest of St. Petersburg, where she resided after the death of Alexander III. Herman Bang has written about his audience with her there.

Of course, it will be relevant to ask me whether I believe that the Russian narrative is true. I can only answer that with a new question: What does it mean for a narrative to be true? Should we take Ranke as a basis – or should we look at it more broadly? If by “truth” we mean the whole truth and nothing but the truth – in a legal sense, I know of no storytelling that can live up to that. The whole truth is a very broad concept. I’m not Russian, I have different assumptions and see different angles – and there are certainly angles I don’t see. I have studied German history (many different narratives), Danish history and American history in depth. So I’ve encountered many different narratives of the same story, seen from different points of view. Which one is the best? It is the narrative that corresponds to the needs of the population and takes into account the population’s preconditions and the angle from which the population must necessarily view history. In short, it is the narrative that benefits the people and society – not necessarily Ranke’s bloodless, laboratory-like narrative that seems to have no purpose beyond itself. It is merely a useless academic exercise. Every people has a right to its own history. No stranger is qualified to tell the “full truth” about another people’s history! Both the concept of truth and the concept of history are too complicated and comprehensive for that. But one thing is certain. If you put an ideological mask over history and try to adapt history to ideology and your own preconceived but ill-founded opinions, you will miss the truth. That’s what Lassen accuses Putin of doing – but that’s actually what Lassen himself is doing!

Lassen begins his book with a thesis. Now, it would be good academic practice to conclude with a discussion of whether or not this thesis holds water in light of the book’s material. This is not how Lassen ends his pamphlet. It is like this:

If Russia is to one day finally abandon war as a national idea and step out of the centrifuge of suffering, it will require – among many other things – a self-reckoning like the one Germany went through after World War II. With a reckoning and a mapping of war crimes. But the politics of history must also be brought before a judge, and the history books must be rewritten. Once again. Streets and squares will be renamed, Stalin statues toppled (for the second time) and the Red Army taken down from its pedestal. “Burn this shit down,” Pussy Riot says about the TV tower in Moscow’s Ostankino… which spreads Kremlin propaganda on state-owned channels, and maybe that was a good idea too. Likewise, the repressed past must be brought to light: imperial racism, the oppression of colonialism, the terror of Ivan the Terrible, the Gulag, the Holodomor and the similarities between Stalinism and Nazism, the War Cult must be dissolved. Likewise, the myths and messianic self-understanding that have dominated Russian historiography since the Middle Ages: “Holy Russia”, “the divine Tsar”, “the Russian soul” and “Moscow as the third Rome” etc. must be dismantled. And the notion that Kyiv-Rus (sic.) is the birthplace of modern Russia must be called what it is: absurd. The politics of imperial history “made us sick” writes Mikhail Zygar, it made us “high on our pride”, but “we fled from reality”. And not least (sic!) Russia has run away from its responsibilities. Most recently the war crimes in Chechnya, Georgia and Ukraine.

What is needed is a cool and critical history policy that is geared towards the deputinization of the whole of society: from the sandbox to the school to the strategy papers of the Security Council and ultimately the Constitution. A history policy that is based on professional historical methods and not myths, and wher

e history books should not serve a military-patriotic purpose. No more viewing history as consisting solely of great personalities, great victories and great sacrifices. Not history therapy, but history recognition. It looks like it’s going to be a long road.

For Lassen, characters are good or evil, and the perception of history is also black or white. But history is only unambiguous to a very limited extent. The Reformation took place in 1536. That is not debatable – but almost everything else about the Reformation is debatable. Lassen is unable to discuss anything because he is completely ignorant. That’s why he has a completely square view of history – and he’s not alone, because this view is also politically determined. It reflects a sick attitude, an absolutist attitude – the desire for total spiritual dictatorship. He genuinely believes that he knows best how Russians should perceive their history – even though their historical conditions are completely different. A country is not only trapped by geography – it is also trapped by history. When he talks about history policy being based on professional historical methods, it can only be said that Lassen has no idea what that means. If he did, he would probably have written a better book – a book that consisted of more than transcripts from other books. In this context, the very word ‘historical politics’ is inflammatory. It means that history is determined politically. In other words, the writing of history is ultimately determined by the courts – as is the case in Germany. He says it himself: history and the politics of history must go before a judge – the country must be “de-Putinized”. Lassen is actually a supporter of historical dogmatism – precisely what he wrongly accuses Putin of being. He has nothing against dogmatics – as long as Lassen’s own politically determined dogmatics apply. And it is universalist – one size fits all. For Lassen, professional historical methodology is – excuse the expression – a city in Russia!

It is a completely unsubstantiated postulate that the Russians have committed all the “war crimes” he lists. He knows nothing more than what he sees on Danish state-controlled television, which gets its news from CNN or other American “sources”. I have traveled a few hundred thousand kilometers around Russia without finding a single statue of Stalin – except for the bust on his grave at the Kremlin wall, to which there is no general public access. But surely a bust in Stalingrad is also appropriate? When I was in Stalingrad, there was no bust, but that was some years ago. A few pages ago, Ivan the Terrible was a democratic pioneer whose ideas could help topple Putin’s regime – now he’s suddenly just the creator of Russian Intelligence – and that’s not meant as a compliment. It is interesting that he mentions similarities between Nazism and Stalinism. There was an exhibition on the subject at the Pushkin Museum in Moscow (and later at the Historical Museum in Berlin) a number of years ago, and it is clear that you can find similarities in architecture, art and other external appearances, which can also be found elsewhere – but there are no ideological points of contact. Another sign of Lassen’s ignorance. There is no war cult in Russia either – but Russians do not forget – and should not forget – the Great Patriotic War. Lassen has no idea what that war meant – none at all. He is a spoiled child of welfare Denmark, completely incapable of understanding other people’s lives and circumstances. Perhaps he should read some better books – or maybe visit some war museums in Russia and Belarus. There are plenty to choose from. But it’s impossible to explain anything to Lassen. I do hope he never gets a visa to Russia! He doesn’t deserve it!

Russia is used to being attacked. Twice by Germany in a century, once by France, once by Sweden – countless times from the east. War cannot be written out of Russian history either. Russia is sacred to the Russians – just as Denmark should be to the Danes! And the great personalities mean far more than the bird droppings. But I think Lassen is actually writing about the wrong country. “Racism and colonialist oppression” – that’s not Russian. Here again is something Lassen owes documentation for. It’s something European and later American.

This is where you have to ask yourself what good is this history writing going to do? It will only create insecure people in a divided and insecure society. It would only be a political tool to break down the individual’s sense of belonging to the nation. There is no objective history writing if you abandon Ranke’s principles of not judging and condemning!

And here we are at the heart of the matter. Lassen wants to change Russians’ perception of history – and thus Russian society. How about starting with the American perception of history, as I mentioned above. Russia does not demand that others conform to Russian ideas. Russia does not see itself as “the exceptional nation” that everyone else must follow, not as a nation that “must lead the world” to create “freedom and democracy”. It is the United States, the most festering boil on world history ever. Lassen feels sorry for Russian war movies – many of which (especially the Soviet ones) are excellent. Few countries have glorified war and mass murder as much as the US. The US has 800 military bases around the world, but reserves the right to prevent others from establishing such bases in the Western Hemisphere (the first half of the Monroe Doctrine. The second half says that the US should stay out of the Eastern Hemisphere, but that half is forgotten). The US organizes regime changes all over the world, overthrowing governments at will. And it is often precisely democratic governments that are overthrown if they do not play along with the American tune. For example, Mosaddeq in Iran in 1953 because he raised the price of oil. In his place they installed the Shah, whose repressive regime they actively supported – until the Shah also wanted more for his oil. Then they let him fall too, but were a little taken aback by developments. Then you paid Saddam Hussein to wage a war against Iran for 8 bloody years. Then you subsequently got rid of Saddam. They set the entire Middle East on fire to weaken the Arab world against Israel. Along the way, they murdered millions of innocent civilians.

And that’s just one example. The US has left a bloody trail across the globe for the last 100 years.1 If the practices of the Nuremberg and Tokyo trials were applied, not a single American president would escape the gallows. And numerous generals and politicians would follow suit. But there is one rule for the US – and another for everyone else.

Today, American weapons actively support Israel’s genocide against the Palestinians.

All in the name of goodness. I wonder if a rewriting of American history and the American self-perception and a change of regime was needed? And here at home, we could, for example, start with the history of the occupation – before we start lecturing the Russians about their history.

If we had a nationally conscious history education in schools in this country, we would have had no immigration problem, no pride parades, no gender confusion, no climate idiocy or other pseudo-issues. We would have had a young generation that didn’t worry about their pronouns and didn’t have tattoos, nose rings and horns on their foreheads because they have to create a unique personal identity – we would have had a generation without diagnoses, a generation that saw themselves as part of a bigger entity that is more important than themselves. A confident, purposeful generation. We would have had a generation that put the good of the whole above the good of the individual. Denmark would have had a future!

Morten Lassen has written a poor and completely superfluous book, based on the sick notion that we – or rather the USA – are the only ones who have seen the light, so we should all adapt to their universalist ideas – a rather colonialist idea. Yes, Lassen is not really a historian, but an advocate of an ideology that he wants to spread to the whole world, just as the Soviet Union wanted to spread communism – unlike the Russians, who just want to be left alone. The book wouldn’t have passed as a thesis in my student days. He consistently follows a single line from page 1 onwards – and it’s all based on quotes from others whose sources cannot be easily checked, and which he himself has hardly checked. It would have been wise for Lassen to study the sources himself. In fact, that is what he does. He follows the official narrative, there is not one independent thought in it, no discussion of even the most absurd notions. The book is not even suitable as toilet paper. Gads Publishing House should be ashamed of itself. This publication should have been strangled at birth. Lassen should be advised to write only about what he knows. That way we should be spared further publications from his hand.

Povl H. Riis-Knudsen

Translated by means of AI

***

Notes

- List of numerous US military interventions 1890-2024: (Chart in Danish) https://www.leksikon.org/art.php?n=3940&t=512 ︎ ↩︎