This article was originally published in Danish on November 9, 2025.

BOOK REVIEW:

Jens Jørgen Nielsen:

KRIMS HISTORIE (The history of Crimea).

Hovedland 2025, 288 pages.

The book is sadly only in Danish. However, the article should still be relevant to those interested in the subject.

Jens Jørgen Nielsen is known as an expert on Russia, and I have previously reviewed his book Rusland på tværs (Russia Across) from 2021, also published by Hovedland. It is still highly recommended. With Krims historie (The history of Crimea), he continues and updates his previous work, as it is difficult to write about the history of Crimea without touching on the war between Russia and the West (because it is not primarily just a conflict between Russia and Ukraine).

Crimea has always been of great strategic importance, and the early history of the peninsula is a mixed bag. Several peoples have passed through Crimea and left their mark. These are particularly tangible in the form of a long series of Greek ruins and remains of Greek cities (e.g., Chersonisos (Khersones) outside Sevastopol) and fortifications built by Italian city-states. Of lasting significance were the settlement of the Tatars and the formation of the khanate centered in Bakhtchisaray, as well as the Ottoman Empire’s victory over Byzantium and the subsequent takeover of Crimea and part of the hinterland. It was in Chersonisos that the Slavic prince Vladimir the First was baptized in 988, thereby converting the Slavic peoples to Christianity, but Germanic tribes also settled in Crimea, and in 1589, a Flemish merchant visiting Crimea wrote down a number of unambiguously Germanic words and a few grammatical observations as evidence that a Germanic language was still spoken in Crimea. However, based on the approximately 85 words included in the records, it is not possible to reconstruct the language, which today is most often referred to as Crimean Gothic1, a further development of the Gothic language spoken by the Germanic tribes who are believed to have lived between the Elbe and Vistula rivers until they migrated south during the Migration Period, brought down the Roman Empire, and founded the Ostrogothic and Visigothic kingdoms (in present-day Italy and the Iberian Peninsula, respectively), where they perished after being absorbed by the local peoples, who constituted a large majority. Large-scale colonization is – no matter how you look at it – the road to extinction.

The presence of the Goths in Crimea interested the Germans when they occupied the peninsula during World War II. Himmler sent an army of archaeologists to try to find traces of these Goths, and plans were drawn up to transform Crimea into an SS order state called “Gotenland.” Indeed, the book shows an official map of Crimea where all place names have been replaced with German names: Sevastopol is Theoderichshafen, Yalta is Adolfsburg, and so on up the coast to Alarichshafen (Feodosia) and Baudilaburg (Kerch). We know what was to happen to the population from Hitler’s monologues in the Führer’s headquarters. They were to be exterminated or decimated several times over, so that there would still be some servants left…

If anyone is surprised that, in the midst of an existential war, money and manpower were spent on such pipe dreams, I can well understand it. It was no wonder that the war was lost. And this was not the only insane project that was brought into being. I could mention a number of much more costly projects, but that would go beyond the scope of a review of this excellent book.

After World War II, Stalin exiled the Tatar population to Uzbekistan on the pretext that they had supported the Germans – which cannot be said to have been the case unequivocally. The Chechens were deported from Chechnya for the same reason. The deported Crimean Tatars were only allowed to return several years after Stalin’s death in 1953, but many never returned, and today the Crimean Tatars constitute a relatively modest minority in Crimea. Instead, Russians and Ukrainians in particular immigrated to Crimea, which has a pleasant climate and had already developed into a popular holiday resort during the Tsarist era. In 1954, Khrushchev decided to transfer Crimea to the Ukrainian Soviet Republic. Jens Jørgen Nielsen believes that this was a well-considered decision and not a spontaneous whim of the leader, as the decision had been made in advance by the Communist Party.

In any case, the transfer did not take place in accordance with the Soviet constitution, and of course there was no referendum in Crimea. It can therefore be argued that this transfer was not legally valid. In the Soviet Union, however, the affiliation had no major practical consequences, but in Crimea there was a mood for returning to being an independent Soviet republic, as it had been previously, but these efforts came to nothing due to Ukrainian resistance.

When the Soviet Union began to fall apart, Gorbachev drafted a proposal for a new Soviet constitution and put it to a referendum. Typically, Crimea and southern and eastern Ukraine voted in favor of the new constitution, while northwestern Ukraine voted against it. However, the constitution never came into effect. The Soviet Union collapsed, resulting in a number of independent states. In January 1991, a referendum on independence was held in Crimea. 93.2% voted in favor of independence. The Ukrainians would not accept this, and Crimea had no army. Instead, they were granted autonomous status. When a new referendum was held in December 1991, this time on Ukraine’s independence, there was really nothing to vote on. The Soviet Union had effectively ceased to exist, and Ukraine had declared itself independent – with Crimea, which had not been consulted in advance. However, prior to the subsequent referendum, Ukrainian President Kravchuk promised the following:

“Under no circumstances will we accept forced Ukrainization. Any attempt to discriminate on national grounds will be resolutely stopped … Dear fellow citizens: Ukrainians and Russians have lived together in Ukraine in peace and friendship for centuries. The two peoples are united by spilled blood, shared sorrow, and shared joy. Let us be worthy of our ancestors. Let us build an independent Ukraine as a common home for Ukrainians and Russians and other nationalities living here.” (History of Crimea, p. 134).

54% of Crimea’s residents voted in favor—there was no alternative, but voter turnout was very low. The residents of Crimea had already indicated that they wanted to be independent – or part of Russia – as the vast majority were Russians. Efforts to achieve independence continued – and the political differences between Kiev and Simferopol grew steadily. Northwestern Ukraine was Ukrainian in terms of language, culture, and sense of ethnic belonging, and strong nationalist movements gradually emerged here, including Svoboda (meaning freedom). The European Parliament commented on these movements in December 2012 as follows:

“The European Parliament expresses its concern about the growing nationalist sentiment in Ukraine, as reflected in support for the Svoboda party … The European Parliament recalls that racist, anti-Semitic and xenophobic views are contrary to the fundamental values and principles of the EU. The European Parliament therefore calls on the democratic parties in the Ukrainian parliament not to cooperate with or support any coalition that includes this party. (History of Crimea, p. 146).

Apart from the fact that this really is none of the European Parliament’s business, as it is an internal matter for a sovereign state, and Ukraine is not a member of the EU, one can only wonder at the change of attitude that has taken place! Today, it is Svoboda and its allies who rule Ukraine and receive massive financial support from the EU! When the Russians call these forces “Nazi,” this is thus fully in line with the assessment of the European Parliament.

It is hatred of Russians that the Russians associate with “Nazism,” because that is the part of “Nazism” they have experienced the consequences of. One could, of course, add that National Socialist ideology does not in itself contain hatred of Russians, but that is irrelevant, because in Hitler’s version it did. Hitler considered Slavs in general to be subhuman. I need only refer to the infamous pamphlet “Der Untermensch”, which was so crude that it was too much even for Himmler, who promptly had it banned – even though it was published by “Der Reichsführer-SS, SS-Hauptamt”! In addition, of course, these forces under Stepan Bandera’s leadership had collaborated with the German occupying power and were thus guilty of treason. Svoboda and the other so-called right-wing parties have no other agenda than “death to the Russians”, from whom the Ukrainians can hardly be distinguished under a microscope, and with whom they have shared history and culture for centuries, just as they have intermarried. This conflict has been artificially created by Europe’s enemies. Europe can only survive if Europeans stand together, regardless of what language they speak and which church they attend.

Well, back to the history of Crimea. With the “Orange Revolution,” the West’s first attempt at “regime change,” Ukrainization began. Ukrainian was to be the only language, and a couple of dubious historians were tasked with rewriting the country’s history from scratch. The project did not really succeed at first. The country had serious economic problems and was largely ruled by oligarchs who plundered the people regardless of language. This was a development that was also seen in Russia, but there they were fortunate that Yeltsin appointed Putin as his successor – and Putin is competent. None of the Ukrainian leaders were competent, and the country fell into poverty. Anyone who visited Ukraine before the war could not fail to notice this. Ukraine’s president, Viktor Yushchenko, therefore appointed the Russian-speaking Viktor Yanukovych from Donbas as prime minister, a position from which he advanced to president in the next election. He attempted to pursue an economic path that involved trade relations with both Russia and the Russian bloc of independent states and with the EU. Most of Ukraine’s national product was generated by the large industries in eastern Ukraine, which were geared towards serving the Russian market. These industries would not be able to survive in the EU. Brussels rejected a compromise, and this, together with NATO’s goal of admitting Ukraine into the alliance in order to encircle Russia militarily, triggered the American-funded and American-organized coup d’état known as the Maidan uprising, in which the legally elected president Yanukovych was ousted and an agreement on peaceful new elections was scrapped. The illegitimate government that was now formed resumed the Ukrainization program. However, Crimea has never been Ukrainian, and there has always been a Russian majority and a majority in favor of affiliation with Russia in one form or another. The UN Development Program prepared a report on Crimea and concluded that 80% wanted to join Russia. Ninety percent of schools in Crimea were Russian-speaking, only 7% were Ukrainian-speaking, and 3% were Tatar-speaking. Now they were all required to speak only Ukrainian.

The events in Odessa, where a Ukrainian mob burned 41 young Russians to death in the trade union building – without being prosecuted – made it clear to the residents of Crimea that this was now serious. They could not live in the new Ukraine. Added to this were the rabid Tatars’ demands that Crimea should belong only to the Tatars. They now wanted their independence! In Russia, too, the developments were viewed with concern. Sevastopol was home to the Russian Black Sea Fleet, and even though a lease agreement had been signed until 2042, there was a fear that Sevastopol could be taken over by NATO.

Russia supported the Crimean residents in their desire for independence – and possible later admission to the Russian Federation. There is much talk about the “green men” who came over on the ferry from Kerch, but the Russians were already present in large numbers in Sevastopol. The Crimean citizens used their partial autonomy to sever ties with Ukraine – and later sought admission to the Russian Federation. This was not an annexation – it was the people’s right to self-determination in action, a secession similar to Kosovo’s secession from Serbia – with the help of NATO. But that has been completely forgotten. It does not fit into the narrative.

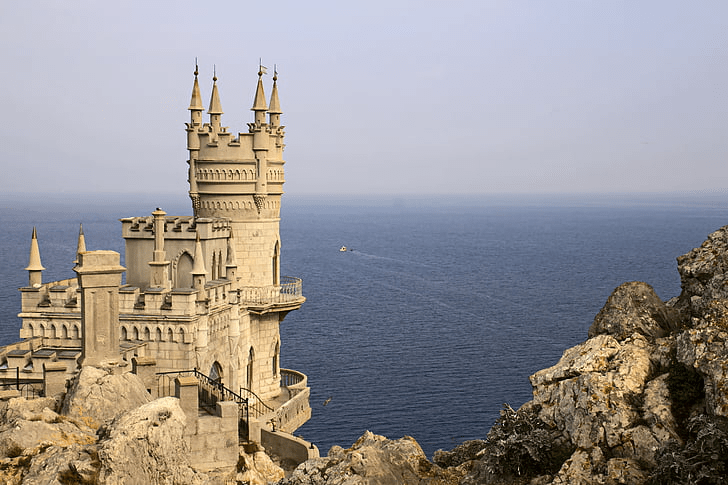

Today, Crimea has three official languages that can be used freely in all contexts: Russian, Ukrainian, and Tatar. I have not heard a single Ukrainian word in Crimea. In 2001, 10% of the population spoke Ukrainian, but I would guess that many have since moved away. However, there have also been newcomers to Crimea, mainly Russians, of course, but also quite a few Germans. Since seceding from Ukraine, Crimea has experienced significant economic growth, a much-needed renewal of its infrastructure, and a thorough renovation of its cities. No one in Crimea wants to return to Zelensky’s Ukraine—especially not when you read Ukraine’s plan for what will happen once Crimea has been “liberated”:

- Changing all street and city names and removing all memorials related to Russia.

- Anyone who has passively or actively supported the Russian occupying power will lose their right to vote.

- Anyone who has worked in the public sector will lose all employee rights, including the right to a pension.

- Requiring all countries, including Russia, to extradite individuals considered to have violated Ukrainian law.

- Journalists and other “experts” must forfeit any property and pensions they may have.

- Deportation of all individuals who moved to Crimea after 2014.

- All agreements, including property deeds, etc., entered into after 2014 will be invalid.

- Demolition of the Kerch Bridge.

- Purging and re-education.

- Removal of anything reminiscent of Russia, including the Russian language.

- Reconstruction of what the Russians have destroyed.

- Sevastopol will be called Object No. 6 for the time being.

When reading this “plan,” one can only conclude that Olexei Danilov, the head of the Ukrainian Security Council who authored the plan, lives in the same drug-induced dream world as Volodymyr Zelensky himself when he fantasizes about defeating Russia. They live in an unreal universe that is completely cut off from the realities on earth. In this context, one is reminded of Hitler, who in the end sat in his bunker in Berlin and commanded regiments that had long since ceased to exist. Incidentally, this plan is remarkably similar to the SS plan for Gotenland. It is just as unrealistic, and in order to realize Danilov’s plan—which would also include all the other Russian-speaking regions—one would also have to follow the Austrian model’s plan to exterminate the Russians. It would be impossible to carry out this idiocy without killing at least a large part of the 90% of the population who today consider themselves Russian and who do not want to be Ukrainianized. Thankfully, this plan has about as much chance of succeeding as a snowball in hell, but it underscores that there is absolutely no possibility of making peace with the current regime in Kiev. There can be no peace in Europe as long as there is a country where such ideas are state policy. A state can only be defined as the home of a people – not on the basis of random lines on a map. If it is impossible to avoid the creation of national minorities when drawing borders, these minorities must be treated with respect and have the right to live in their own language and with their own culture.

Point 11 is particularly laughable. The Russians have not destroyed anything. They have rebuilt a neglected peninsula with dilapidated buildings and worn-out infrastructure. But Mr. Danilov has obviously not been to Crimea recently.

In any case, this gives us an insight into what our tax money is being used to secure in Ukraine – the new “European values” that Mette Frederiksen talks so much about. In 1945, such ideas were considered a “crime against humanity.” And for which people were hanged slowly.

With Krims Historie (The History of Crimea), Jens Jørgen Nielsen has set himself a major task. Not only is the history of Crimea itself complicated, but when you also have to go through the recent history of the entire relationship between Russia and Ukraine, the narrative necessarily becomes quite comprehensive and condensed when it has to be kept to 288 pages. There are several chronological narratives that run more or less parallel, which occasionally makes it difficult to follow a thread that runs across these narratives. This is a book that should be read in its entirety and not as a reference work.

Translated with the help of AI

Note

- German philologist Hans Krahe does not believe that this is a further development of the Gothic language, which we know almost exclusively from Bishop Wulfila’s translation of parts of the New Testament, preserved in various manuscripts, but rather an independent East Germanic language. The basis for reaching this conclusion seems to me to be based on insufficient material – and above all, I find it difficult to see which East Germanic tribes could possibly be involved. (Hans Krahe: Historische Laut- und Formenlehre des Gotischen, 2nd edition, Carl Winter Universitätsverlag, Heidelberg 1967). ↩︎