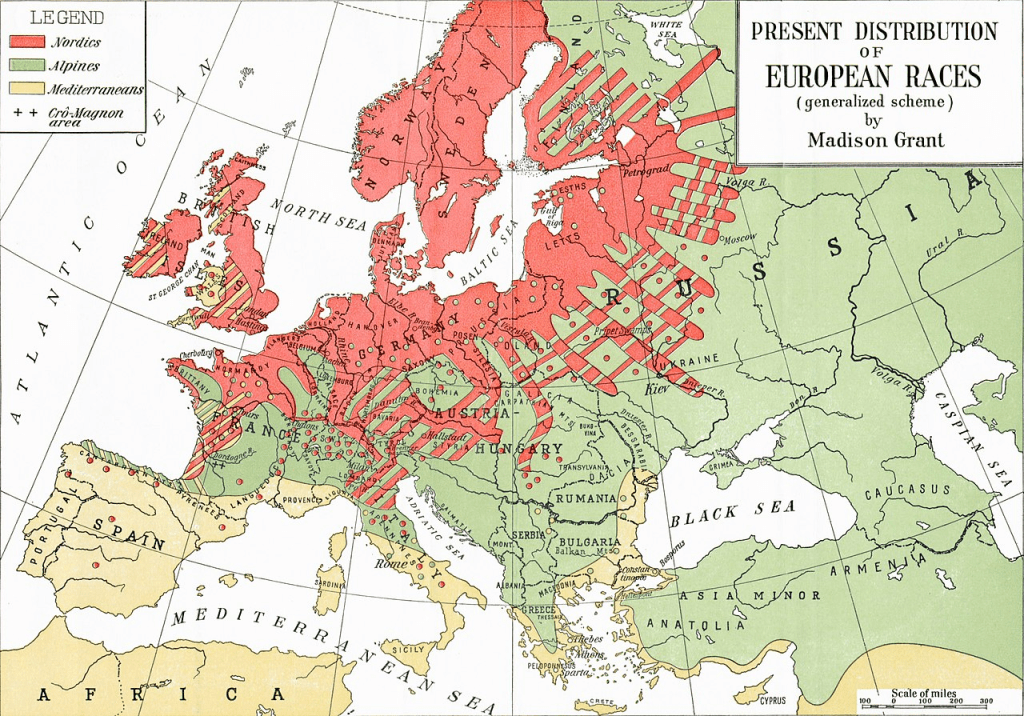

From left to right: Arthur de Gobineau, Houston Stewart Chamberlain and Madison Grant.

(It is in Danish here for our Danish readers)

The following is an article by Ole Kreiberg. He is a veteran in the Danish nationalist movement who has written about the Jewish question and collective white ethnic interests, among other things. We have included links to three books mentioned in the article, which we believe are important historical documentation for our readers.

Ole’s introduction

The following is a speech paper that I wrote for an oral assignment as a history student at the University of Copenhagen. I was given 20 minutes to present the paper orally to the class, who could ask questions afterwards. I showed the literature list below via the overhead projector. As it is a speaking paper, there are no notes.

The approach to this lecture is scientific and thus no attempt to propagandize for or against racism. The main inspiration comes from William Shirer’s work, The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich (the chapter on the roots of the Third Reich), which in the English-speaking world is considered one of the best works written about the Third Reich. This work is 100 percent politically correct, but as it deals with the subject in great depth, it is inevitable that quite interesting issues will be unearthed, for which I have found primary sources. By the way, the assignment was approved.

The history of intellectual racism

By Ole Kreiberg

During the 19th century, Europeans and their descendants came to rule most of the world. This created a sense of superiority over non-European peoples of color – what is popularly known as racism. The word racism is defined, for example, according to Gyldendal’s Foreign Dictionary, as the belief in the superiority and innate right of certain races to rule.

In this climate, philosophies and theories emerged to reinforce this way of thinking. It would prove to go far beyond justifying the superiority of Europeans and their descendants over subjugated peoples of color.

The first major breakthrough for intellectual racism came from the French writer and diplomat Arthur de Gobineau, who between 1853 and 1855 published a four-volume work entitled “Treatise on the Inequality of the Human Races”. Gobineau, who was born in 1816, was an orientalist by training and worked in the French state administration, specifically diplomacy. Gobineau is often referred to as the spiritual father of racism – a term whose legitimacy is disputed, however, which I will return to later.

Prior to Gobineau, linguists had classified a wide range of languages from Europe to Bengal in India as Indo-European based on a number of commonalities. Gradually, the idea also emerged that the various Indo-European languages also corresponded to an Indo-European people. They envisioned an original Indo-European indigenous people who had once spoken the same language and belonged to the same race. Over time, this people had spread from Central Asia, where it was believed to have had its original home, to Europe and much of Asia and the Middle East. The original language evolved into dialects and then into completely independent languages within the Indo-European language tribe. Indo-Europeans also mixed with the non-Indo-European peoples they subjugated and thus came to look different depending on where you were in the world. This idea is central to Gobineau’s work and that of his successors.

The word Aryan, which is used in Gobineau’s work and that of his successors, comes from the ancient Indian language Sanskrit and means noble. The word first appears in the Rigveda, which is the oldest sacred scripture of the Hindus and the oldest scripture in an Indo-European language According to Hindu tradition, this scripture was written 5000 thousand years ago. According to Western science, it is believed to have been written between 1500-1200 BC.

The word is mentioned here in connection with the Central Asian people who conquered northwestern India around 1700 BC.

Now I’d like to briefly talk about ancient India and the concept of Aryans, as the word Aryan originates from here along with the idea of Aryan superiority.

The ancient Indian civilization, like the ancient Persian civilization, was created by Indo-European white conquerors who called themselves Aryans (Sanskrit: aryas). These Aryans penetrated India from the west – from what is now Afghanistan and Iran. From here the Aryans had come even further back from Central Asia – specifically Western Turan according to G. S. Ghurye (see bibliography).

The caste system in India was later founded, among other things, to prevent the Aryans from being biologically mixed with the original colored majority population. In Sanskrit, the word for caste (varna) also means color. In Indian scriptures (by Patanjali) from as late as the centuries around the birth of Christ, the highest caste, i.e. the Brahmin caste, is described as having golden brown hair, and in other ancient scriptures (sastras) the Brahmin skin color is described as white.

The ancient Indian (Aryan) civilization had a great influence on the rest of Asia. For example, the famous temples of Angkor Wat in Cambodia and Borobudur in Java were built after the Indian model. The introduction of Buddhism in China was accompanied by a very strong and profound Indian cultural influence. Buddhism originated in India and grew out of the ancient Indian (Vedic) religion and philosophy, much like Hinduism today. To the west, the Arabs from Brahmin India, along with a whole lot of basic math, learned the number system including the zero that we use today.

Despite the strict Indian caste system, the castes were still more or less mixed and the result is the India we know today. According to a recent UN statement, the Indian caste system is a form of racism, and Manu Smriti, the ancient Hindu religious code that defines the caste system, has also been labeled racist by the UN.

Back to Gobineau:

The word Aryan, originally used in the West to refer to Indo-European languages, came to be used to refer to the white race through Gobineau in particular. According to Gobineau, there were no pure Aryans, only different degrees of purity. Already around the year 0, the last pure Aryan populations would have been mixed with non-Aryans. However, in Gobineau’s view, the Aryans themselves were nothing more than the cattle nomads they were originally thought to have been. It was only when they mixed with non-Aryan peoples that they began to develop higher civilization. As the Aryans mixed more and more with non-Aryan peoples, their inherent Aryanity was diluted and the higher civilization they created perished. Thus, according to Gobineau, all higher civilization stems from the Aryans. In Gobineau’s own words, it is explained thus. I quote: “History shows that all civilization proceeds from the white race – that no civilization can exist without the complicity of this race”. Another quote reads: “The race question dominates all other problems in history …. The inequality between the races is sufficient to explain the whole evolution of the destiny of peoples.” Gobineau saw the Nordic race as the least mixed part of the white race. This is where the idea of blond and blue-eyed Aryans originated. In his view, the Nordic race was most strongly represented in northwestern Europe, more specifically above a line roughly along the Seine and eastward to Switzerland. It thus included part of the French, all the English and Irish, the people of Holland and Belgium, the Rhineland and Hanover, and all Scandinavians. He excluded the Germans who lived south and southeast of this line, i.e. the majority of Germans. On the other hand, he considered the Germans who lived within this line to be the best Aryans. He found that the Germans brought improvement wherever they went. This was true even in the Roman Empire. The so-called barbarian tribes who defeated the Romans and split their empire did civilization a distinct service, for the Romans in the fourth century were almost entirely degenerate (i.e. too heavily mixed with non-Aryans, while the Germans were relatively pure Aryans): “The Aryan German” he declared “is a strong creature …. Everything he thinks, says and does is therefore of essential importance”. Gobineau’s ideas were quickly taken up in Germany, which during this period was coalescing into a cohesive nation state. The composer Richard Wagner, whom Gobineau met in 1876, enthusiastically endorsed them, and soon Gobineau associations sprouted up all over Germany (but not in France). However, Gobineau was only a philosopher and writer. He had no political program or plan for the betterment of the race. In a way, he can be compared to the later Oswald Spengler, who believed that all cultures will inevitably perish. Gobineau believed that miscegenation was inevitable and would eventually lead to the downfall of all higher civilization and ultimately even to the extinction of humanity. Gobineau’s view was deeply pessimistic, but his racial philosophy had a profound influence on his contemporaries and beyond.

At the aforementioned Gobineau Society in Germany, a person soon emerged who would be influential in developing Gobineau’s thoughts and giving them the direction we normally associate with German Nazism and negative racism. This man was Houston Stewart Chamberlain, who is often referred to as the strangest Englishman who ever lived. He was the son of an English admiral and married to the daughter of composer Richard Wagner. For various reasons, he was drawn to Germany as a young man, where he settled permanently and became German in thought and language. He wrote a number of works, but the one that would become most famous in this context was the 1899 work Grundlagen des Neunzehnten Jahrhunderts – a work of about 1200 pages. This work was something of a sensation and brought him sudden fame in Germany. It quickly became widespread among the higher classes, who, according to William Shirer, seem to have found exactly what they wanted to believe. Within ten years it went through eight editions and sold 60,000 copies, reaching 100,000 before the outbreak of the First World War. It experienced a resurgence during the Nazi era. By 1938, more than a quarter of a million copies had been sold.

Like Gobineau, whom Chamberlain admired, Chamberlain found the key to history, indeed the basis of civilization, in the race. Chamberlain’s teaching is as follows: To explain the 19th century, i.e. the contemporary world, one must first consider what was inherited from distant times. Three things Chamberlain said: Greek philosophy and art, Roman law and the personality of Christ.

Chamberlain counted the Celts and Slavic peoples as Aryans, although the Germans, i.e. the Teutons, were the most important element in this context. However, he is unclear in his definitions and states at one point that “he who behaves like a Germanic is a Germanic regardless of his racial origin”. Perhaps he was referring to his own non-German origin. In any case, he believed that the Germanic was the soul of our culture.

The longest chapter in the work deals with the Jews. Although he begins the chapter by condemning “stupid and disgusting anti-Semitism” and a little later declares that the Jews are not inferior to the Germans but only different. They have their own greatness; they realize man’s sacred duty is to guard the purity of the race. Yet he ends up going really far. According to Shirer, a significant part of Nazi anti-Semitism stems from this chapter.

Chamberlain writes that, finally, the road to salvation lies with the Germans and their culture, and of the Germans, the Germans are the best equipped, for they have inherited the best qualities of the Greeks and Indo-Aryans, i.e. the ancient Indians. This gives them the right to be masters of the world. “God builds today on the Germans alone,” he writes in one place.

Among the book’s first and most enthusiastic readers was Emperor William II. He invited Chamberlain to his palace in Potsdam and at their very first meeting they struck up a friendship that lasted until the end of the author’s life in 1927. This resulted in an extensive correspondence between the two men. Some of the 43 letters Chamberlain wrote to the Kaiser (who replied to 23 of them) were lengthy essays that the Kaiser used in several of his bombastic speeches and declarations. Chamberlain constantly reminded the Kaiser of Germany’s mission and destiny and announced that Germany will conquer the world by internal superiority. For all this writing, Chamberlain, who had exchanged his English citizenship for German in 1916 in the middle of the First World War, received the Iron Cross from the Kaiser.

However, this Englishman’s influence was greatest on Hitler’s Third Reich, whose coming he foresaw. Hitler laments in Mein Kampf that Chamberlain’s ideas were not appreciated more in the Second Reich, i.e. the Reich founded by Bismarck. Chamberlain first met Hitler in 1923 and wrote a letter to him the next day in which he wrote, among other things, that great tasks await you. Chamberlain quickly joined the Nazi Party and began writing for its publications. In one of his 1924 articles, he hailed Hitler, then in prison for his part in the Munich beer hall coup, as being destined by God to lead the German people. Chamberlain’s 70th birthday was celebrated with a five-page tribute article in the Nazi magazine “Völkische Beobachter”, which hailed his work as the gospel of the National Socialist movement. Chamberlain died 16 months later and apart from a prince representing the abdicated Emperor William II, who was unable to return to Germany from exile abroad, Hitler was the only official person present. According to Shirer, who worked as an American foreign correspondent in Nazi Germany, Chamberlain was considered by many contemporary Germans to be the spiritual founder of the Third Reich.

As for Gobineau and Chamberlain, I will quote from Shirer: “Let it be said at once that neither of them were charlatans. They were both men of extraordinary knowledge, deep culture, and well-traveled. Hitler’s anti-Nazi biographer, Konrad Heiden, who deplored the influence of Chamberlain’s racial doctrines, writes that he was one of the most astonishing talents in the history of German intelligence, a goldmine of knowledge and profound thought.

It was not only in Germany that racist thinking was widespread at this time. It was all over the Western world – especially in the United States, which had a large colored population. Many states in the US had apartheid laws that banned white-on-black marriage and much more – despite the US being the first democracy in recent history. For the first hundred years or so of its history as an independent state, the democratic United States tolerated Negro slavery. After its abolition, many states introduced apartheid laws that remained in place for the next hundred years of US history. As mentioned, racism was widespread in the US, and the US had its own equivalent of Gobineau and his treatise on the inequality of the races in Madison Grant’s 1916 work entitled The Passing of Great Race, which was widely read and accepted in contemporary America. The same was true of South Africa, which was allied with the US in World War II against Germany. After participating in the defeat of Nazi Germany, South Africa introduced one of the harshest apartheid systems the world has yet seen. Before World War II, Sweden had a state institute for racial research established by a Social Democratic government. Among other things, this institute researched racial differences between Lappish and non-Lapish Swedes. So racial ideas are by no means something reserved for totalitarian states.

As this topic is very extensive and I only have twenty minutes, I will limit the rest to Germany and Austria.

While Gobineau and Chamberlain represented some of the most decent ideas by contemporary standards, in Germany and Austria in the late 19th and early 20th centuries there was a whole undergrowth of societies and lodges that dealt with the same theme but in a somewhat more outrageous way. The English professor Nicholas Goodrick-Clarke, who won his doctorate with a thesis on mystical German and Austrian sects and right-wing ideology in the 19th and first half of the 20th century, has written the following work: The Occult Roots of Nazism, subtitled The Ariosophists of Austria and Germany 1890-1935. The racist fantasies of Guido von List Jörg Lanz von Liebenfels and their influence of Nazi Ideology.

While Gobineau and Chamberlain had been more philosophical and ideological, racist movements with a more religious, cultic and occult tinge also emerged in parallel. These movements often had their origins in theosophical thought, which views religion as a whole and believes that all religions have a grain of truth in them. For example, it was the Theosophical movement that brought the Indian swastika sign, i.e. the swastika, to Europe. The Theosophical movement emerged at the same time as the wave of nationalism and racism in the latter half of the 19th century. The word theosophy is made up of the Greek words theo + sof, meaning God and wise respectively. Theosophy is not concerned with race or nationality but nevertheless provides inspiration for Ariosophy, which is a philosophy that sees the divine in the Aryan or, perhaps more accurately, a religious philosophy that fits the Aryan and is more or less opposed to Semitic religiosity, which is expressed in Christianity, Judaism and Islam. These latter religions, according to Ariosophy, suppress or alienate the Aryan from his true nature. Ariosophy is the teaching that is supposed to liberate the Aryan spiritually.

Guido von List was the first popular writer to combine German nationalist (völkisch) ideology with occultism and theosophy. Guido von List was born in 1848 in Vienna. He developed his own occult philosophy based on something he called Armanenschaft – an Odinist religion that he believed the Ancients in Europe had practiced. But it would take too long to go into that too.

One of List’s followers was Jörg Lanz von Liebenfels, who soon began his own occult activities. He published numerous books and a very extensive pamphlet series entitled Ostara containing racist, occult, theosophical and ariosophical topics. He gave his own peculiar explanation of how miscegenation had originally occurred based on his interpretation of texts in Mesopotamian cuneiform. I won’t go into that in detail. What is interesting is the question of his influence on the young Hitler. In 1932 Liebenfels wrote in a letter to a Frater Aemelius: “Hitler is one of our students”. It is uncertain how much Hitler knew about Liebenfels and his writings. Liebenfels himself claims that Hitler and his childhood friend, August Kubizek, visited him in 1909 and bought a stack of his pamphlets. According to psychologist Wilfried Daim, who wrote a biography of Hitler in 1947 entitled Das Ende der Hitler Mythos, based on an interview with Josef Greiner, who is said to have known Hitler in Vienna, it is claimed that Hitler had a stack of Ostara in his room at least 25 cm high. Greiner’s testimony is disputed. After the war, only one book by Lanz, “Das Buch der Psalmen Teutsch” from 1926, was found in Hitler’s library.

More interesting in connection with Hitler was the Thule Society in Munich, which was one of many ariosophical societies in Germany and Austria. The Thule Society used the swastika to symbolize the Aryans and were the first to use the term National Socialism. However, the use of the swastika in this context can be traced back to the aforementioned Guido von List. The members of the Thule Society were mostly from the upper and middle classes, but they wanted to spread its ideas to ordinary workers. Therefore, the Deutsche Arbeiterpartei (DAP) was founded. Hitler first met this party on September 12, 1919. As a veteran of the First World War, Hitler had gotten a job as a spy in military intelligence. His job was to monitor extremist groups. He became so enthusiastic about this party that he gave several speeches at its meetings in the years to come. It was here that his oratorical talent was discovered. Together with the Thule Society, Hitler was instrumental in merging the National Socialist Party and the German Workers’ Party into the National Socialist German Workers’ Party. He also helped decide that the swastika should be of the Buddhist type with the arms facing clockwise.

However, Hitler didn’t much care for these ariosophs, which he referred to in Mein Kampf and in other contexts as Völkische fantasts. When the Nazi Party came to power, several of them were banned from writing, and some went into exile or even ended up in concentration camps. It is now clear that the racism associated with Nazism was not Hitler’s invention but was already widespread at the time. It was part of the mindset of the German nationalist factions that Hitler united into one party. Hitler himself was more of a practical man of action than a real thinker. He was more of a German chauvinist than a racist, although of course he accepted racism.

The lecture ended here and questions could be asked. As I was sure that there would be questions or comments about the Jews in the context of racism, I said the following to anticipate the course of events:

Now many will probably ask what he really thought about the Jews in this respect. You can read the following in his political testament, which he wrote a few months before his death:

“Our racial pride is not aggressive except where the Jewish race is concerned. We use the term Jewish race as a convenient term because in reality and from a genetic point of view there is no Jewish race. In the meantime, however, there is a group to whom the term can actually be applied and which is used by the Jews themselves. It is the spiritually homogeneous group to which all Jews throughout the world belong, regardless of the country they live in. It is the group that we refer to as the Jewish race. …. The Jewish race is first and foremost an abstract race of mind…. A race of mind is something more solid and durable than a mere race.

Bibliography

William L. Shirer: The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich, Copenhagen 1966

Joseph-Arthur de Gobineau: Selected Political Writings, London 1970

Houston Stewart Chamberlain: Foundations of the Nineteenth Century, New York 1986

A. L. Basham: The Wonder that was India. London 1982

G. S. Ghurye: Caste and Race in India. Bombay 1932

M. N. Dutt: Manusmriti, Varanasi 1979

N. Goodrick Clarke: The Occult Roots of Nazism. The Ariosophists of Austria and Germany 1890-1935, Wellingborough, 1985